I have always loved vintage beads. Many of my favorite vintage beads were made in Germany. Here is an old article from a past issue of The Ruby about the Gablonz Jewelry Industry by Alison Schmidt.

Enjoy!

-Ava

There is something undeniably exciting about finding vintage beads. Although it seems that there is a plethora of them to be had, as time carries on the supply is obviously dwindling. These precious artifacts of days-gone-by are being happily hoarded by bead lovers everywhere, and many contemporarily-made beads are inspired by, or even reproduced from, vintage beads. It would be easy to disregard the history behind beads and simply enjoy them, but their story is so fascinating- how could we?

Although Gablonz was economically stable from the mid-nineteenth centruy to the mid-twentieth century, politically it was anything but. The citizenship of the Gablonzers changed three times in a single generation: prior to WWI Gablonz was part of Austria-Hungary; afterwards it became a part of the Czechoslovakian Republic; and as a result of the Munich Agreement in 1938 it was incorporated by Greater Germany (culturally the vast majority of Gablonzers were of German descent). The bead and jewelry industry stayed strong throughout these changes. It wasn't until the end of World War II that the Gablonz endured the most drastic change of all, which would end the first chapter of its life.

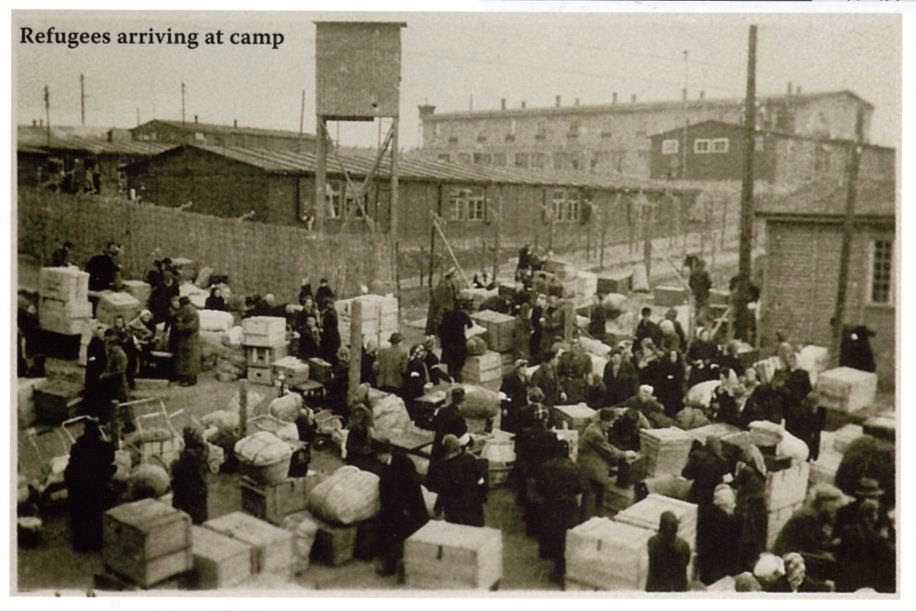

In 1945, as a wrathful retaliatory move against Germany, the Gablonzers' Czech neighbors drove them from their ancestral home and moved into the area, renaming it Jablonec. The displaced citizens of Gablonz were moved to refugee camps (run by US soldiers), and then were sent all over Germany and Austria. This would, in effect, prohibit the Gablonzers from reestablishing their companies. After they had expelled or murdered the people of the Gablonz, the Czech nationalized all German property, which included the glass and jewelry manufacturing equipment that had been left behind. The Czechs took over Gablonzer factories and shops, attempting to salvage the bead industry. Occasionally Gablonzers were brought back to train the Czech workers, but ownership and income had changed hands.

Meanwhile many displaced glass and bead making Gablonzers had been sent to a refugee camp in the town of Kaufbeuren, in the German state of Bavaria. The camp was made up of Army barracks and was manned by American Soldiers. About 25% (roughly three-million people) of Gablonz ended up in Bavaria at these temporary camps. As families, homes, and businesses were lost, so it seemed were the last traces of hope. But in spite of their trying circumstances the Gablonzers persevered in their new, unfamiliar locale. They took their beliefs about what could be considered jewelry materials to heart by using things they found in the barracks and out in the surrounding forests. These refugee quarters were soon decorated with jewelry made from wood, seeds, and scrap metal gathered from tin cans and crashed airplanes.

The Czechs had hoped the Gablonzers would take up new careers- but such was not the case. One man, in particular, devoted himself to reestablishing the bead industry. Erich Huscka was a native Gablonzer whose parents had owned a necklace firm. He spoke fluent Czech, and by listening to Prague Radio while sitting in his Munich refugee camp he was able to discern what exactly was happening with his hometown and his people. He worried about the future of not only his own family, but also for the traditions of his culture. Being a man of great ambition, Huschka was able to talk his way out of American captivity. Left for broke, he began driving a taxicab for money. With this small income he was able to start looking for a place to restart the Gablonz industry in Bavaria.

After much searching Huschka found the perfect setting for the Gablonz renaissance. While driving on Bavarian back roads he came across an abandoned dynamite factory in Kaufbeuren. The plant was comprised of more than 100 huge bunkers and spanned over 640 acres. The most incredible thing about it was that it had escaped any injury during the war. It was heavily camouflaged by a think fir forest and much of it had sod roofs. At the end of the war the American Government had tried to destroy the factory, but destroying a building designed to produce dynamite proved difficult; and so, it sat- unused.

Finding the owner of this prime piece of real estate was Huschka's next challenge. Its original owner was a company that no longer existed. It then fell into the hands of the German Reich, but the Reich also no longer existed. The American Government was in possession of the area, but did not want to lay any claim to the old factory; furthermore, they were in agreement with the Czech Government at the time and were trying to prevent the Gablonzers from reinstating their homeland industry. The US turned the property over to the Bavarian State Government, possibly to avoid any more involvement. Huschka's charm once again prevailed, and after much work the state released the abandoned dynamite factory to him. He was then able to convince the two local governments to allow the refugees to reestablish there. Within a year they had the proper permits, and the Gablonzers set out to reclaim their reputation as the world's most illustrious bead makers.

There is an old superstition among glassworkers that goes back to the 16th Century: the glass trade will not thrive unless it exists in a region with evergreen trees near mountains. The legend was based in economic reality: the mountains supplied quartz, lime, and silica sand; while the trees gave potash and charcoal- all important glass-making ingredients. The land Huschka had acquired for the Gablonzers had both evergreens and mountains. About sixty bead and glass makers followed Huschka to the new premises, and by the summer of 1946 the work of rebuilding their industry had begun.

They managed to clear enough space to setup workshops, began with one generator and a water pump, and built a "gypsy" glass oven from old rails. By autumn they sixty-person workforce had expanded to 600, and the abandoned dynamite factory was bursting with life. The population on the grounds grew to over 1000 in a single year; the original four family businesses turned into more than ninety. The area became more than a factory: it became the city of Neugablonz (New Gablonz).

The same amount of success did not come to "Old Gablonz" that the Czechs had taken. As a result of several issues in world politics- the largest being the Communist Party's infiltration of Czechoslovakia a few years later- Jablonec could not successfully recover the jewelry industry it had seized from the Gablonzers. Regardless, a small portion of the industry still exists there, and several bead makers thrive elsewhere in the country (Czech glass beads are some of the most popular beads found today). The Gablonzers flourished in their new city because those who couldn't bring anything else could at least bring their skills and knowledge of the craft. Neugablonz is also a major hub of the bead world in the present today.

Our Family's Story

Thomas Muller* is a third-generation glass and bead maker from Neugablonz. Muller's grandfather, Huyer, was a very important glass maker in pre-World War II Gablonz. His specialty was kmposit glass, which, in English, would be called composite glass- meaning the glass rods were made up of different colors and transparencies. At that time, Huyer was the only person who had the capability of creating this exact type of glass, so he kept his recipes and methods well guarded.

Although Huyer was a successful businessman he was not immune to the persecution the Gablonzers felt during and afte WWII. When the citizens of German descent were being pushed out of Gablonz, Huyer was one of them. he and his wife were given one hour to whatever belongings they could carry before they were taken to a refugee camp along with their three-year-old daughter (Muller's mother). Huyer knew that the recipes for his komposit glass were very valuable, and he didn't want the Czech Government to steal his techniques. Hopeful that he would be able to start his business wherever he ended up, he wrote down his recipe on a piece of fabric and stitched it to his pants.

After the refugee camp, Huyer and his family made their way to Austria, where they were able to establish a glass bead and stone company. Unfortunately, in order to have enough funds to launch his company Huyer had to sell his glass recipes to a German company. Meanwhile, Muller's great uncle started a glass bead factory in Neugablonz. Muller's mother went to worker there and that is where she met her husband- Muller's father. After working together there for a few years they married and started their own company. The company still thrives in Neugablonz to this day.

After the refugee camp, Huyer and his family made their way to Austria, where they were able to establish a glass bead and stone company. Unfortunately, in order to have enough funds to launch his company Huyer had to sell his glass recipes to a German company. Meanwhile, Muller's great uncle started a glass bead factory in Neugablonz. Muller's mother went to worker there and that is where she met her husband- Muller's father. After working together there for a few years they married and started their own company. The company still thrives in Neugablonz to this day.The Gablonzer Industry in Today's World

There are several points of historical interest in Germany and in the Czech Republic that honor the Gablonzer industry (both old and new). Jablonec is home to the Museum of Glass and Costume Jewelry, and in Neugablonz there is the Isergenbirgs Museum Neugablonz, as well as the Gablonzer Industrie Jewellery Route.

The Museum of Glass and Costume Jewelry is comprised of three separate buildings around Jablonec that hold exhibitions of glass and jewelry, manufacturing, and history. The main Art Nouveau building holds a large collection of glass, jewelry, coins, and medals. There is also a library that holds both historic and current documents about the glass and costume jewelry industry. The Belveder Gallery is one of the oldest baroque building in Jablonec. It has exhibitions of buttons, glass, and costume jewelry, as well as national history and geographic exhibits. The Memorial of Glass Making in the Jizera Mountains is now a place to learn about the history of glass production, including a model of a glass settlement.

The Isergebirgs Museum Neugablonz illustrates 400 years of Gablonzer industrial history, focusing on both old Bohemian Gablonz and Neugablonz. Its main focus is on the story of the Gablonzers' expulsion from their old city and the establishment of the new. The museum holds artifacts from Neugablonz's primitive beginnings, including jewelry made of food cans, shards of glass, and potato dough. The exhibition also documents economic and social change as represented by Neugablonz jewelry products. The Gablonzer Industrie Jewellery Route is a tour of factories, shops, and studios that still exist in Neugablonz. it covers the complete spectrum of the industry by showing an array of examples from handcraftsmanship all the way to industrial mass production.

The next time you look at your collection you might wonder where your vintage German and Czech beads actually come from. Is that old Czech cut really Czech, or was it originally a Gablonz design? Could your vintage beads have been smuggled out of Jablonec during the exile? The next time you run your fingers over new German or Czech beads, you might feel the weight of generations. Even if the exact origin of vintage German or Czech glass beads could never be truly determined, at least their tumultuous history can always be honored.

The author is thankful for the various literature provided by the museums listed above, the history books, and an extremely helpful 1952 Saturday Evening Post article by James P. O'Donnell. She also wholeheartedly thanks Ava and Justin for collecting absolutely invaluable word-of-mouth accounts from current bead and jewelry makers and museums curators in Neugablonz. Photos courtesy of Iserbirgs Museum Neugablonz.

*Thomas Muller is an alias

No comments:

Post a Comment